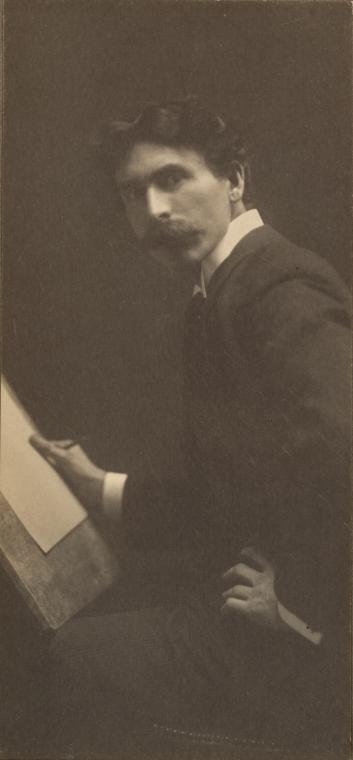

If Ernest Thompson Seton’s father hadn’t decided to quit the ship business to be a gentleman farmer, or if he’d decided to go straight to Toronto from England to take up accounting, Ernest Thompson Seton would never have discovered the wonders of nature in Kawartha Lakes, he wouldn’t have aspired to study natural history or animal anatomy or woodcraft. He wouldn’t have become the man he did.

But his relationship with his father was strained at best.

Despite the abuse he received, Seton was not unkind toward his father when writing his autobiography. He almost paints his father as a victim of his father:

My father (born September 6, 1821) was an honourable man of high ideals and remarkable personal force. He was proud of his noble descent; but often he checked himself speaking of these things, as they savoured of worldly vain-glory.

By nature refined and scholarly, he loved books and art, and had aspired to a university career. But my grandfather, a rugged man of the business world, could not see the need of it. He had made his own fortune out of a small inheritance, and had had only a grammar-school education. So he bluntly told my father that he himself had succeeded without a university career, and he did not propose one for his son.

TRAIL OF AN ARTIST-NATURALIST: THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF ERNEST THOMPSON SETON (1940)

Ernest states that his father had no vices. Selfish was his personality.

He had, however, one or two peculiarities which did not vanish with age. He was very indolent, had a marked craving for “proper respect”; and was, I think, the most selfish person I ever heard of or read of in history or in fiction. He was so selfish that he thought himself generous in feeding his family, so important that the most vital interests of his family were always cheerfully sacrificed to his most trifling passing convenience. His own father had been a masterful rugged man and a stern disciplinarian; therefore my father, not considering that he was treated with proper respect at home, had left the paternal roof at the age of twenty-two, and married Alice Snowdon, my mother, then twenty years of age (born December 1, 1823).

Mother was a beautiful woman with a strange diversity of gifts—profoundly religious, full of energy, yet weak in character; and before they had been wedded a month, they two were one—and that one was my father.

TRAIL OF AN ARTIST-NATURALIST: THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF ERNEST THOMPSON SETON (1940)

Beatings from his father drove Ernest to seek refuge in nature, even after they relocated to Toronto.

After one of the worst beatings given by my father I got away from the house as fast as I could. I hoped soon to quit it forever.There was only one place to which I could go for quiet—for absolute aloofness; that was my cabin, far off in the woods. Here I could ponder and plan in peace; without doubt, temporary residence in that cabin would be a part of my plans for escape.

TRAIL OF AN ARTIST-NATURALIST: THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF ERNEST THOMPSON SETON (1940)

When Ernest became depressed, his mother sent him to spend his summers with the family that bought their Kawartha Lakes’ farm, the Blackwells. The people of Kawartha Lakes were kind to him, and Ernest began to wish William Blackwell was his father.

Ernest wanted to study natural history, but his father wanted him to be an artist. So out of revenge, Ernest decided to be the best artist, better than the others. In addition to his day studies, he took night classes at the Ontario School of Art. He succeeded with highest marks in all of his subjects and a gold medal for his art.

It was a proud moment for me and for my father, but also a turning point. I took advantage of my victory to say in brief: “Now I have taken highest place in the highest school in Canada. If I am to be an artist, I must take the next step, that is, study in London.”

There was no gainsaying my reasoning; and Father replied: “I’ll send you to London for a year at least. I will talk it over with your mother and brothers, and see what we can allow you. But it will surely be the least possible you can live on, and must be considered merely a loan to be repaid later.”

Just what I was to get he never would say definitely. But Mother realized the embarrassment of my position, and told me privately: “You shall have five pounds (twenty-five dollars) a month, if we can possibly spare it.”

TRAIL OF AN ARTIST-NATURALIST: THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF ERNEST THOMPSON SETON (1940)

Ernest got his art education in London, but very little money to live on. He became the cliched “starving artist”:

So far as money was concerned, I was as hard put as could be. My father had intimated that I should have sixty pounds a year to live on. But he never sent it. I had no regular allowance. He never sent me anything except in response to a prayerful letter telling how badly off I was, and that all my cash was gone. The whole amount he advanced in two and a half years was eighty pounds (four hundred dollars).

In London I made a few shillings by illustrating occasional books for the publishers, Cassell, Petter & Galpin, but it was a trifling addition to my income.

Ten pounds for my two ocean passages came out of all this, so that thirty pounds (one hundred and fifty dollars) was my annual income to meet all expenses. Books and art materials were necessaries of life, so I saved on such non-essentials as food and clothing. Consequently I was always ill-dressed and hungry.

My constant study was economy. Meat was high-priced in England, so I gave it up. My breakfast was usually a bowl of porridge with milk, a cup of coffee with a slice of bread and butter. The coffee was a beverage of my own fabrication—a compound of bran, molasses and beans, pounded up together, then roasted into a hard loaf. A piece of this the size of a walnut gave the colour of coffee and something of the taste to a cup of hot water.

My lunch was commonly half a pound of white beans, occasionally varied with a few raisins or dates, the actual cost of the same being six cents. This meal was usually eaten in the British Museum as I sat on one of the benches or under the shadow of Memnon.

My dinner in my own room was a big bowl of bread and milk, sometimes supplemented with one slice of bread and butter.

My total weekly expenses for living were generally under two dollars, to which must be added six shillings (one dollar fifty cents) for my room and care of the same, which included the cooking of my porridge and the heating of my morning coffee.

TRAIL OF AN ARTIST-NATURALIST: THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF ERNEST THOMPSON SETON (1940)

Ernest was poor, but happy. He spent his days drawing at the Museum and eventually convinced them let him get a membership to their library so he could study their volumes on natural history.

Then he had to return home. At age 21, Ernest’s father presented him with a bill for every cent spent on his life, plus interest:

One day, after I had been home long enough to recover from the immediate effects of the voyage, my father called me into his study. He took down his cash-book, a ponderous and aged volume, opened it at E, and then made one of his characteristic speeches:

“Now, my son, you are twenty-one years of age; you have attained to years of manhood, if not of discretion. All the duties and responsibilities which have hitherto been borne for you by your father, you must now assume for yourself. I have been prayerfully rememberant of your every interest, and I need hardly remind you that for all that is good in you, you are, under God, indebted to your father—and of course, to some extent, your mother also.

“For this, you must feel yourself under a bond of gratitude that will strengthen rather than weaken as life draws near the goal that all should keep in view. You owe everything on earth, even life itself, to your father; reverent gratitude should be your only thought. While it is hopeless that you should ever discharge this debt, there is yet another to which I must call your attention at once.”

He now pointed to page after page in the cash-book—the disbursements that had been made for me since my birth. There they were, every item with day and date perfect—unquestionably correct—even the original doctor’s fee for bringing me into the world was there. The whole amount was five hundred and thirty-seven dollars fifty cents.

“Hitherto,” said he, with traces of emotion at the thought of his own magnanimity, “I have charged no interest; but from this on, I must add the reasonable amount of six per cent per annum. This I conceive to be a duty I owe to myself as well as to your own sense of duty and manhood; and I shall be glad to have you reduce the amount at the earliest possible opportunity.”

I was utterly staggered. I sat petrified. Most men consider that they owe their sons a start in life. My father thought that his father owed that to him; but his case, he felt, was different.

There was the awful sum, every item reasonable and exact. Nothing was said about my grandfather’s money, or my mother’s twenty thousand dollars—both received by him and not accounted for. In the last, at least, I had a definite stated interest of two thousand dollars.

TRAIL OF AN ARTIST-NATURALIST: THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF ERNEST THOMPSON SETON (1940)

This was the end of their relationship. Ernest tried to gain his father’s favour by reverting to Seton name, a name attached to royalty that his father hadn’t gotten around to assuming, but their relationship only deteriorated.

Although he could have paid off most of his bill immediately, Ernest decided to hold onto his money. His father had made it apparent that he wasn’t welcome at home any longer, so Ernest decided to use his funds to leave home and begin life on his own.

At age 30, after his brother ran into trouble and sold his property near Port Credit that included a cabin where Ernest had an outdoor life and practiced his art, Ernest decided to leave Ontario again.

I had, however, bought some Toronto real estate. This I managed to sell for one thousand eight hundred dollars. With four hundred and fifty of this, I paid my father a last instalment, in full, of all his claims for educating and bringing me up. Then, with my steamer ticket and one thousand two hundred dollars cash, I set out for the East, arriving in London, England, June 11.

TRAIL OF AN ARTIST-NATURALIST: THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF ERNEST THOMPSON SETON (1940)

Ten year later, at age 40, Ernest had made a name for himself, discovered success as an author and illustrator, and earned “not only enough to insure comfort for myself and family, but also sufficient to enable me to help numerous relatives who were less fortunate, and especially to take care of my father and mother.”

When he was 42, Ernest’s father passed away. He’s buried at Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Toronto.

Read more about Ernest Thompson Seton and his live in Kawartha Lakes here: Ernest Thompson Seton.

Pingback: 2023 in Review